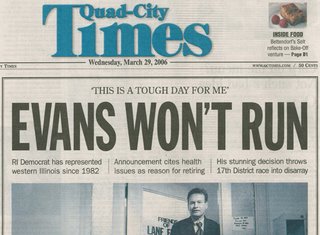

Rock Island, Illinois, isn't much of a city these days. There's little industry or retail, and the geography prevents residential expansion. But there are bars . . . quite a few of them. And they create problems.

Rock Island, Illinois, isn't much of a city these days. There's little industry or retail, and the geography prevents residential expansion. But there are bars . . . quite a few of them. And they create problems.

There was a time when Rock Island was a transportation and manufacturing hub. Farm equipment was the major industrial player, as well as trade in lumber and other building materials. Those were endeavors that created tax revenue, but throughout the 70s and 80s, those industries finished their exodus. Today the city relies upon its downtown "arts and entertainment district" to generate the majority of its commercial tax revenues.

They can label the area whatever they want, but here's what it boils down to: Rock Island — one of several small cities in the "Quad City" area that straddles the Mississippi River — keeps its bars open until 3 a.m., which is 1-2 hours later than any other local community. It's a goldmine for bar owners who welcome Davenport and Bettendorf, Iowa, bar-hoppers on the weekend and the city opens its arms with a 1% liquor and food upcharge on the sales tax just to make the welcome complete.

As you might expect, there is a price to be paid when drunk people from around the area converge on a few city blocks to finish off their weekend reveries. Yes, fights break out, low-lifes abound, and people do lewd things on the streets. To this point, city leaders have asked bar owners to participate in a voluntary — and then mandatory — annual fee for extra police presence on the weekends. Now they've taken the extra step that many other communities have pursued: blanketing the area with security cameras.

It's an interesting dichotomy for a City Council that has been controlled by a strong mayor (who regularly spouts "moral" ideals) for nearly 20 years. Late night liquor hours invite trouble, the kind of trouble that is expensive to regulate. So the city welcomes the tax revenue the after hours drinking provides while passing most of the security costs along to the bar owners who are the very ones who make the municipal fiscal windfall possible.

So, predictably, security cameras have suddenly become the easy answer to downtown problems. The city is spending $17,000 to have an unspecified number of cameras installed by June 1, just in advance of the busy festival season — a cost that will ultimately be passed along to local bar owners, no doubt.

The decision to proceed with this plan was made just a few nights ago amid (what seems) very little opposition. Although video surveillance in public places has yet to attract federal regulation, it's a practice that will undoubtedly eventually come under legal scrutiny.

The Supreme Court has steadfastly held (most notably in Katz v. United States 389 U.S. 347, 88 S.CT.507 [1967]) that there is no expectation of privacy in a public place, and it's difficult to disagree with the point that when you are in public, you forfeit your rights to privacy. But now that question has become more difficult. We are near (or are already on top of) technology that can basically perform an electronic strip search at a hundred feet. The devices in use are surpassing simple video surveillance, and the courts will eventually need to become involved in these issues.

The ACLU, on its

Web site, provides 4 well-argued reasons for opposing public video surveillance. The most persuasive might be the first: that video surveillance has not been proven effective in deterring crime. The most compelling reason, though, is the last: that video surveillance will have a chilling effect on public life. This outcome, which is the least quantifiable, may prove be the most important and the one that most deeply affects quality of life in a democratic society.

Out here in flyover land we value our liberties to a degree that people in major cities may have surrendered long ago. We're not up to no good, we have nothing to hide, but we just feel a comfort in knowing that the freedoms this country was founded upon are alive in their purest form out here. We're not ready to give up our daily movements to constant surveillance.

When communities in our own backyard begin to experiment with public video surveillance, it makes many of us more than nervous . . . it makes us wonder what's next. And that's the question this whole issue of public, traffic, and corporate surveillance begs: what is next? The ACLU, in all of its liberal glory, is telling us to imagine the next step, and even though they haven't spelled out the future explicitly, we've all read the books, and we know.

Maybe a few cameras outside bars in the middle of the night will help us find out who started a couple of fights a year, but is that information valuable enough to put mechanisms in place that create a society under the microscope in all public places, at all times?

Or is it just this simple: you keep your bars open until 3 a.m., you're going to have a few drunken fights a year. Want to change that behavior? Think about altering your drinking hours instead of threatening more of your citizens' civil liberties.

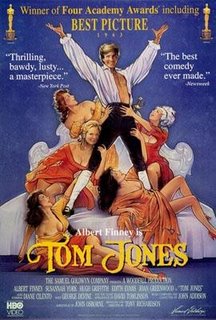

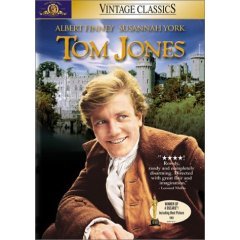

At number 5 of The Guardian's 100 Greatest Novels of All Time sat Tom Jones. He seemed innocent enough. He'd even won an Oscar. How bad could he be?

At number 5 of The Guardian's 100 Greatest Novels of All Time sat Tom Jones. He seemed innocent enough. He'd even won an Oscar. How bad could he be?